Survival of the Slowest—now at The Fleet Science Center

Being slow can be a good thing. In fact, some creatures’ very survival in the wild depends on it.

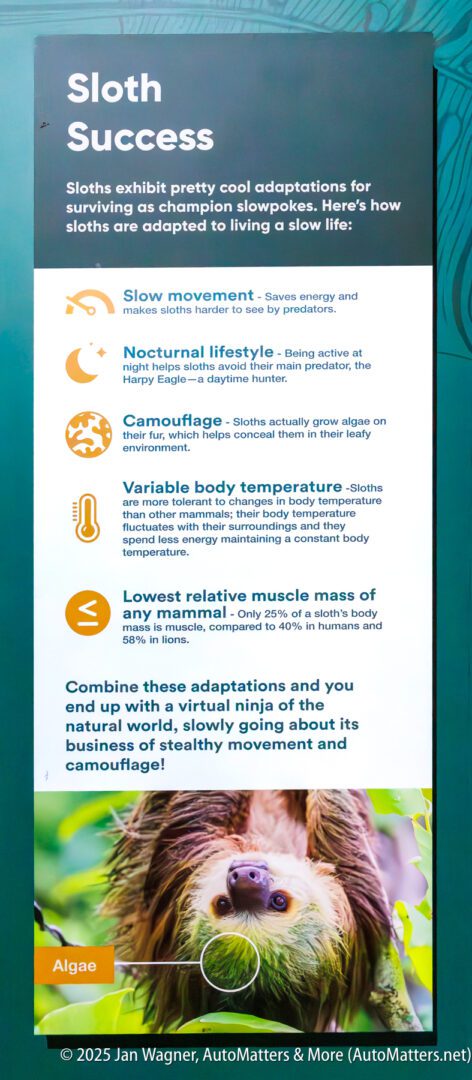

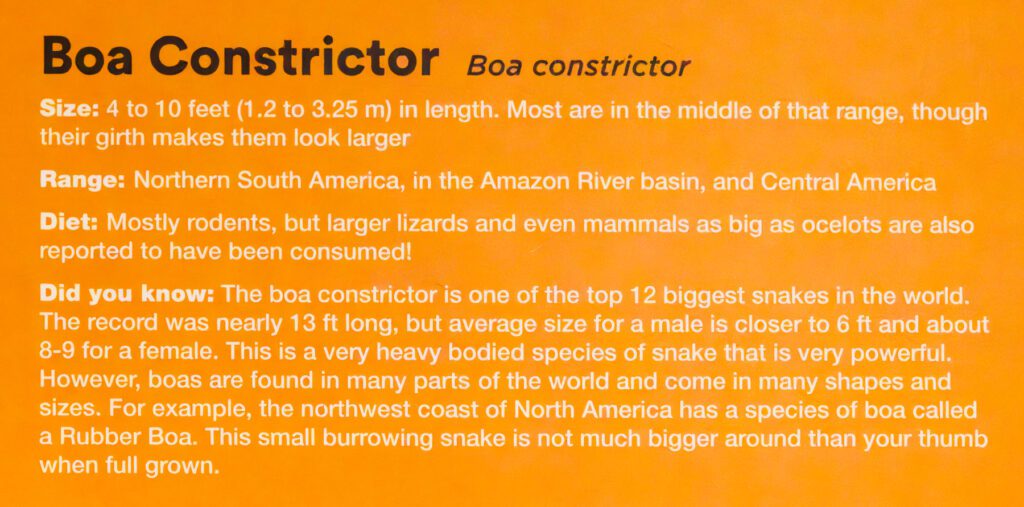

“Survival of the Slowest” is the newest exhibit at the Fleet Science Center. It features live animals housed inside 19 temperature- and humidity-regulated, natural habitats. The animals include Maple the sloth, Casper the albino iguana and Aphrodite the boa constrictor.

Several of the animals are brought out daily, for interactive presentations led by wildlife educators who travel with the exhibit, care for the animals, discuss their adaptations and survival strategies for slowness, answer questions about them and even help you take selfies with the animals. All of the exhibit’s animals are rescues.

On the day that I visited, we were introduced to a Black Rat snake — one of the most active and social animals in the exhibit. These can usually be found up and down the eastern side of the United States and Canada. They are related to garter snakes.

Their coloration is great for camouflage. If you look inside their enclosure, you will see foliage, rocks and other things that the snake can hide under. In the wild they hide from predators, such as birds and larger animals.

Black Rat snakes can grow in length from three to eight feet. They feel the most comfortable when they coil the bottom half of their body around something — for example, around an arm of the wildlife educator who introduced us to her.

One of their adaptations for self-protection is called musking, in which they can release a very unpleasant, foul odor if they feel threatened.

Even though they are not rattlesnakes, they too can use their tail to create a rattling sound to scare off predators. Since they do not actually have rattles in their tail, they rapidly strike their tail against something solid, like a tree.

Black Rat snakes are carnivorous. Their prey includes smaller rats (more nutritious than mice), as well as squirrels, mice, chipmunks, birds (sometimes quail or chicks) and amphibians.

Black Rat snakes are non-venomous constrictors. If they find a rat, they would bite it on the face, wrap their body around it and squeeze. They do not squeeze until their prey is dead. Rather, they hold the rat by the face to induce fear and panic, causing a heart attack. They continue to squeeze until they feel no movement. Then they swallow their prey whole. To save energy, that can take anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes.

They have a few ways to get the prey into their body. They use their body to push one end of the food into their mouth. They may also use items around them, such as rocks and branches, to help push the food in. They can also use gravity, whereby they sit with their head up and use gravity to pull down the food through their body. Sometimes when they eat you may see a little lump travel down their body. That is the food going all the way to the snake’s stomach, to be digested. Their stomach is a little way past midway down.

At the exhibit, they do “frozen thawed feedings,” as opposed to feeding with live food — for ethical reasons. Also, if the snake was not hungry when they left a live rat in the snake’s enclosure, the rat might get defensive and actually hurt or kill the snake, since they have very sharp teeth which can bite through skin, muscle and bone.

Black Rat snakes do not have to eat every day, which is a helpful adaptation because in the wild they may not find food very often. They can go for months without eating. The snakes in this exhibit eat once every other week.

Their life span is approximately 10-15 years, depending upon the circumstances of their environment. When the weather turns very cold, their metabolism slows down and they enter a state called brumation, which is similar to hibernation but not a deep sleep.

How often they shed their skin depends upon their rate of growth. Younger Black Rat snakes might shed once every other month, whereas older, slower-growing snakes might only shed a few times per year.

“Survival of the Slowest” is included with your admission, and will be at the Fleet Science Center until September 1, 2025. For more information, visit: https://www.fleetscience.org/experiences/survival-slowest.

To explore a wide variety of content dating back to 2002, with the most photos and the latest text, visit “AutoMatters & More” at https://automatters.net. Search by title or topic in the Search Bar in the middle of the Home Page, or click on the blue ‘years’ boxes and browse.

Jan, very interesting. Did they have any snails or slugs? I saw a funny cartoon in the paper recently. I snail was squiggling along a sidewalk, and a sign said “Warning: no rest stops for the next 5 feet”. David.

You know, I do not recall seeing any snails, slugs or escargo.

Jan